8 Reasons Why Price Transparency Doesn’t Lower Healthcare Costs

Would better visibility into costs somehow make healthcare less expensive? Based on a brief recently published by the Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker, it seems that the impact is modest, at best. Here are some of the reasons why price transparency appears destined to fall short. Although necessary and useful, eventually it won’t avoid the need for additional steps to regulate prices.

Since January 2021, hospitals in the USA are now required to provide price information online. Beginning in 2023, insurers will also have to provide rates and cost-sharing estimates for individual, group and self-funded coverage enrollees.

Currently there is no price regulation for hospitals, except in Maryland, where the state sets rates for all payers. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires that hospitals publish these. Unfortunately, they appear to have become akin to the aspirational rates that are sometimes posted inside the doors and closets of hotel rooms. Actual, negotiated rates with payers had often been treated like a trade secret. Once published, there could be dozens of payers that each bill different amounts.

Intuitively, comparison shopping keeps prices down. That might be true if healthcare services were as simple as having a buyer and a seller. In fact, knowing about prices is barely a first step at being able to give patients realistic negotiating power over prices.

There are several practical reasons why price transparency cannot be expected to make much of an impact.

- Complexity. Healthcare prices are fundamentally difficult to understand. Federal rules require that hospitals publish information in a ”consumer-friendly” manner. This is not a friendly topic. Price variations may be explained away in terms of unexplained “pricing methodology”. Merely posting a .csv Chargemaster file isn’t useful. Importantly, there is really no visibility into cost (and margin) rather than prices displayed. Despite attempts to use standard value units, the conflation of cost and price remains problematic.

- Supplier Rivalry. Rules about posting prices are fought by both hospitals and insurers. They argue that it introduces new costs to do so. Realistically, both sides are attempting to capture revenue, and there are strong disincentives to not reveal actual costs. Bargaining power may result in higher prices (Michigan example: Shane Group v. BCBSM)

- Temporal Urgency. Much of healthcare is occasioned by immediate needs, or situations where it isn’t realistic to shop around. Price information is useful for planned services. But emergency services, and complex and specialty care occur unexpectedly. There is no practical way to shop and compare prices.

- Opaque Out-of-Pocket Expenses. Even when prices are posted, they don’t reflect true expenses for the patient. Many intervening variables affect what must be paid. These include whether all the billing providers for an episode are in- or out-of-network, what level of provider is used, and cost-sharing details (deductibles, co-insurance, co-pays, etc.). Patients want to know what they will owe. The listed price is often a meaningless and inflated figure that the provider presents payors before negotiating an agreed fee. Additional expenses can pile up on top of that. Patients are left to coordinate a volley of communications with both the payor and the provider companies to understand what is actually owed.

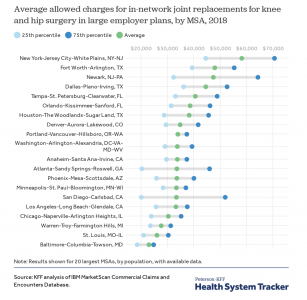

- Limited Impact on Geographic Variability. Price transparency doesn’t seem to address the problem of widely different prices for similar services between nearby settings. KFF found wide variations in prices across metro areas. (KFF looked at the price of obtaining joint replacement, MRI and cholesterol testing). The range of prices is most dispersed in San Diego, and most consistent in Portland. Where are the lowest costs? In Maryland, where hospital rates are regulated, not merely reported. The average price of knee / hip replacements ranges from $58.2K in NYC to $23.2K in Baltimore. (An encounter like a lipid panel is less subject to dispersion).

- Consumer Disregard Patients tend to be unaware of, or don’t use, price transparency tools (Massachusetts example: Pioneer Institute). There is a pervasive assumption that healthcare patients are rational consumers with respect to purchasing decisions. But in a context this complex, there are too many intervening factors. It’s hard to envision a “consumer-friendly” website, when there are so many behind-the-scene factors that are driving prices. Purchasing exchanges for ACA may come closest at accomplishing this. But is more challenging to display trade-offs once an actual clinical need has arisen.

- Ignoring Quality The price comparisons that hospitals post won’t capture perceived quality of healthcare. Even if it were attempted, there would likely be disagreements over what defines quality. Researchers are inclined to look at clinical outcomes. Actual patients think more in terms of what they have heard from people they know. As KFF notes in their brief, in the absence of experience-based information from patients, higher prices may be spuriously interpreted as signifying higher quality.

- Adverse Effects Perversely, publishing comparative prices may actually inflate them. Low-cost providers could match their fees to charge as much as the high-cost providers. The KFF brief calls this out as a particular risk because of “highly concentrated markets” for healthcare in the US. In some communities, insurers compete as virtual duopolies, and transparency may heighten pressure to increase prices. GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office) and Commonwealth Fund are among the organizations that have documented the deleterious effects from lack of actual competition.

Healthcare markets function in distinctive, unusual ways. This is not like purchasing vegetables at a public market. Transparency alone is an insufficient mechanism to reduce costs. To effectively tackle the problem of outsized U.S. healthcare costs, it is hard to imagine solutions that don’t rely on price regulations.

-published March 5, 2021

Write a comment