Cautionary Flags Raised by Aduhelm Approval

The FDA recently approved aducanumab, branded as Aduhelm, to treat Alzheimer’s disease. How this was done raises flags of caution, and reveals troublesome features of healthcare marketing in the USA. Recurrent neglect of these factors will compound the chronic problem of expensive treatments that are not infrequently futile.

This does not mean that the approval was unjustifiable. The burden of Alzheimer’s disease is crushing. Over 6 million USAmericans suffer from the disease, and this number can be expected to increase as the proportion of older adults increases. Since the natural history of each case lasts for years and because the cognitive loss produces extreme behavioral demands, it is easy to see how the manufacturers could argue for more lenient standards to approve this new treatment.

From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository

The first cautionary flag is raised by over-reliance on biomarkers to approve this medication. Another, separate and commercial concern, is how physicians will be incentivized to administer it. Both are instructive because the dynamics aren’t unique to Alzheimer’s disease- even if the stakes are arguably higher in this instance.

The biomarker here is amyloid plaques. These protein deposits in the brain are pathognomic of Alzheimer’s disease. Evidence of their presence is used to establish a diagnosis. Relying on a physical manifestation is, of course, not unusual in medicine. Critics assert that the decision did not adequately weigh clinical markers too. In this instance, the evidence that aducanumab removes amyloid plaques was not so much in question. Evidence that it produces clinical improvements, or slower loss of cognitive abilities, was slimmer. That made this approval contentious.

It is not unusual that biomarkers, or physical findings, fail to line up with measurable clinical outcomes that are cognitive or behavioral. This is rampant in chronic pain management, for example. Positive MRI results that depict a herniated disc exhibit variable correlation to reports of pain, or levels of disability. What can be worrisome is when there is an over-reliance on physical evidence when deciding to intervene with treatment. The demand for pharmaceutical ways to treat Alzheimer’s disease is so great that this approval looked more at a “surrogate endpoint” than the clinical result. In general, it is risky to offer treatments are based on physical evidence rather than knowledge of how it improves the life of the patient. Otherwise, desperate patients may agitate for a fix that proves to be unsafe.

The second cautionary flag is how this may foretell a brushfire in healthcare spending. Most patients with Alzheimers’ disease are Medicare beneficiaries. As it currently stands, Medicare is prohibited from negotiating prices with pharmaceutical manufacturers. Biogen set the price for Aduhelm at $56,000/year. (In other developed nations, pricing review boards exist to establish what the manufacturer can be paid.) As pointed out in The Atlantic, that is a huge cost burden. Because Aduhelm is infused, it needs to be administered in a medical office. Seniors in Part B of Medicare are on the hook for 20% of their outpatient bills- potentially $11,200. In view of expected demand for treatment, even with supplemental (Medigap) coverage, premiums may need to increase substantially to cover this.

Demand may accelerate because of financial incentives for physicians to dispense Aduhelm. Office-based infusions pay out about 6% of the price directly to the physician. Prescriptions under drug benefits (such as Part D) don’t produce direct payments to the prescribing physician. The risk here is that treatment decisions, rendered for patients whose suffering they are understandably keen to relieve, may be biased by the attraction of profit from offering care.

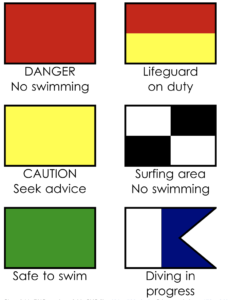

This controversy plays out a script that is likely to recur for other diseases. In this instance, Biogen and Eisai worked hard to secure approvals, so much so that it provoked criticisms that the lifeguard at this beach may have been in league with the sharks. Overt collaboration with patient advocacy groups (notably the Alzheimer’s Association) may be suspect yet it is not unique. That dynamic can be strained because the two stakeholder groups have naturally conflicting objectives when it comes to pricing. Opposing viewpoints came from professional groups, such as The American Geriatrics Society. The Campaign for Sustainable Rx Pricing is an industry coalition that includes AARP, providers (notably AHA) and payors, isn’t a clearly influential group defending overall healthcare patient interests. Public Citizen directed ire towards FDA panel members. Some have resigned.

The FDA stipulated that a Phase 4 program is required to verify that there are not adverse outcomes as a result of using aducanumab. In practice however, interpretation of those results may be subject to the same forms of influence that have affected the current decision. The whole question of what Phase 4 studies really do is an important, and longer topic. These are referred to as “post-marketing” studies, but in fact, marketing doesn’t cease while such studies occur.

As for the cost, this topic is currently gaining some greater visibility in Congress. Once again it is alarming how actual payors- those of us who fund Medicare or pay premiums- have hardly any influence. The incremental evolution of Medicare appears, at times, to have been essentially designed to secure revenue flows for providers. That is also a topic for a broader (and recurring) post, at a later date.

-published June 20, 2021

Write a comment